- Inducted:

- 2011

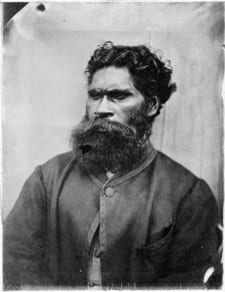

William Barak — 'Beruk' in the Woiwurrang language of his people — had leadership in his blood. At a time when Aboriginal people in Victoria were seen as, at best, a curiosity, at worst an obstruction to the colony's growth, Barak's diplomacy earned him genuine respect and support from white settlers. He also unified Aboriginal people, helping them to face an uncertain future in their irrevocably changed land.

Barak's father, Bebejan, and uncle, Billibellary, were Wurundjeri ngurungaetas, or clan leaders. The latter was a particularly influential figure who, in 1835, joined leaders from the Kulin nation in signing John Batman's treaty. An 11 year old Barak witnessed the event.

Barak is closely associated with Coranderrk, the Aboriginal settlement established near Healesville in 1863. He campaigned for its creation, contributed to its early success as a thriving, self-sufficient community, and was its indefatigable defender until the end of his life. He saw Coranderrk as a way for the Kulin people to maintain a physical connection to their country; a connection he played a key role in educating non-Aboriginal people about.

In 1874, Barak became ngurungaeta and almost immediately had his leadership put to the test. The Board for Protection of Aborigines, which resourced and operated Coranderrk, was under increasing public pressure to break the settlement up; the plan being to relocate the residents to a location on the Murray River. Barak commenced a persuasive and peaceful campaign of letters and petitions to the Government, ably assisted by his nephew Robert Wandin and Thomas Dunolly. He then led a deputation to Parliament House — emulating a historic walk he had undertaken with his cousin and mentor, Simon Wonga, years earlier, when they sought consent to establish Coranderrk.

Barak was granted an audience with Graham Bell, the then chief secretary and future Premier of Victoria, who was suitably moved to facilitate a halt to the closure. Unfortunately, what suffered in the wake of the reprieve was a deterioration of the quality of life at Coranderrk, as the Board mismanaged it to its detriment.

A second march occurred in 1881, spurred on by the poor conditions and further reports that Coranderrk was to be closed. Barak rallied the settlement's 22 able-bodied men, by then drawn from a diverse population of people displaced by other settlement closures. Together they called for the abolition of the Board and sought autonomy in the running of Coranderrk.

A Government Board of Inquiry resulted, to which Barak made a submission. Coranderrk was finally made a permanent reserve by Premier Bell, ensuring its survival until many years after Barak's death in 1903.

Described as wise and dignified, Barack's talents as a communicator were undeniable. He could speak to both the worlds he occupied and unify sworn enemies. By bringing attention to the plight of Coranderrk, he garnered influential non-Aboriginal supporters. In particular, he forged a close friendship with a woman from Scotland named Anne Bon, who over the years assisted him in his various campaigns, and ultimately became an ally on the Board. Barak's life was not without tragedy. He lost two wives and a beloved son. Ann was a great support to him in his grief.

Victoria's settlement had ended Barak's traditional upbringing just shy of his initiation. While his conversion to Christianity testifies to the influence of the various colonial institutions he was channelled through in his youth — from the Yarra Mission School to the Native Police Corps — as an adult Barak's cultural identity proved robust and he used it in the battle for European hearts and minds.

Barak's renown as an artist further boosted his profile. It served the dual purpose of preserving his cultural heritage and educating people. He vividly recreated the corroborees of his memories in the paintings he produced and became known for his displays of traditional skills, such as boomerang throwing. The anthropologist Alfred Howitt spent time with Barak, and his teachings formed the basis for Howitt's book on Aboriginal life, The Native Tribes of South East Australia.

Today, Barak continues to be honoured as an important figure in Victoria's history. A new Melbourne bridge was given his name in 2006. It connects Birrarung Marr — the Yarra land of his people — with the city's sports precinct and is a powerful metaphor for what he achieved between his people and many settlers. Barak's image will also adorn a skyscraper to be built in Melbourne's north.

The value of Barak's efforts to build understanding between two vastly different worlds can never be underestimated. He used his position to defend his people's connection to their traditional land. In his role as diplomat and ambassador, he also proved that Aboriginal people could exert influence on decisions affecting them in colonial Australia.

Updated