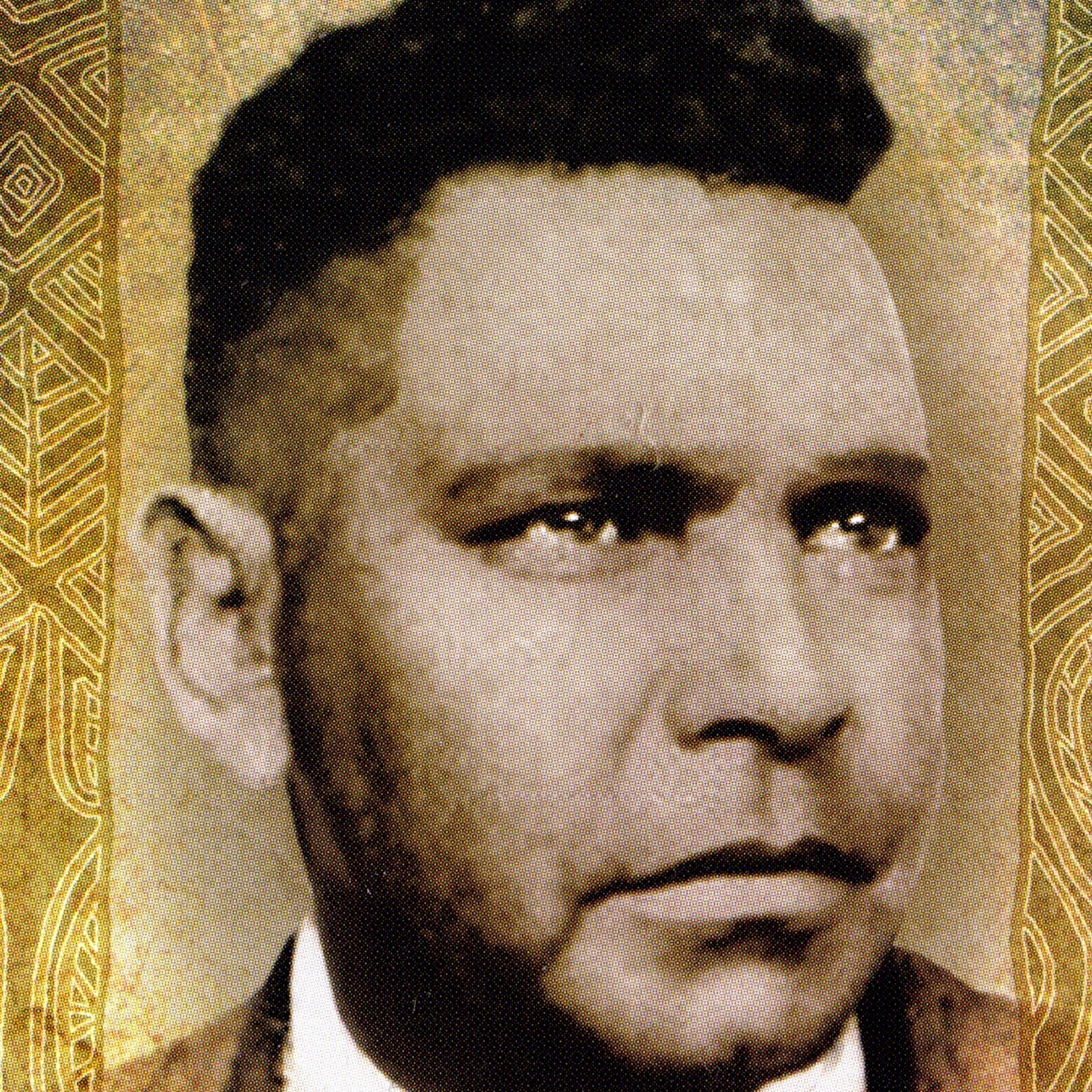

- Inducted:

- 2014

Jack Patten was one of the great Aboriginal leaders of the 20th century and set the agenda for the civil rights movement in Australia. The Yorta Yorta man spoke out against Aboriginal inequality with such vigour that his words resounded across the land.

Early years

Born at Cummeragunja Mission, just across the Murray River in New South Wales in 1905, Jack was the eldest son of John James Patten and Christina Mary (née Middleton). His father was a blacksmith from Coranderrk Aboriginal Station near Healesville, who later became a highly regarded police tracker. From an early age, the importance of education was instilled in Jack and his 5 siblings by their parents and maternal grandfather George Middleton.

Jack attended the mission school at Cummeragunja, followed by state schools in Tumbarumba and West Wyalong. During World War I, he volunteered with the Junior Red Cross, where his natural organisational skills impressed others. Jack's academic potential was recognised with a scholarship that he hoped to use to pursue a career in the navy, however his application was rejected on racial grounds. He took on various labouring jobs instead.

Their plight had a profound impact on Jack

By 1927, Jack was boxing professionally with a troupe that toured the far north coast of New South Wales. He fought under the moniker 'Ironbark'. While travelling around, Jack met his future wife Selina Avery, a Bundjalung woman. The Bundjalung people lived in poverty at the Clarence River Aboriginal settlement in Baryulgil and their plight had a profound impact on Jack. Upon learning that the community's children were excluded from the local school, he gathered together a group of men, physically relocated the schoolhouse and only had it returned when assurances were given that the children would be educated.

Jack and Selina married in 1931 and had 7 children. During the Great Depression they moved to Salt Pan Creek, an Aboriginal squatter's camp in south west Sydney. Jack's father and younger brother George were also living there. Jack gained a good grounding in politics from his father, who was well informed and enjoyed lively discussion around the campfire.

An opportunity to bring to people's attention the disadvantage endemic to his people

By 1936, Jack and his family had settled in the Sydney suburb of La Perouse. Jack was introduced to many notable political figures, including Michael Sawtell and Percy Reginald Stephensen. He saw in them an opportunity to bring to people's attention the disadvantage endemic to his people. A persuasive public speaker, Jack addressed crowds at the Domain each Sunday and also became a prolific letter writer on matters concerning Aboriginal rights.

Jack developed a close working relationship with another Aboriginal leader William Ferguson, who launched the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA) in 1937. Jack was the organisation's first president. He travelled from southern Queensland to western Victoria, visiting Aboriginal reserves and attracting a loyal following. Along the way, he collected and published stories in an effort to highlight the suffering of Aboriginal people and the inaction of the bureaucracy. Jack gave evidence to a Legislative Assembly select committee examining the administration of the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board, which the APA sought to have abolished.

On 26 January 1938, Jack and William Ferguson organised the first Aboriginal Day of Mourning, based on an idea by the Aboriginal leader William Cooper, who also took part. Jack also wrote and edited a short-lived Aboriginal newspaper — the first publication of its kind in Australia. Importantly, he drafted a '10-point plan for Citizens Rights' and led a deputation to present it to Joseph Lyons, the prime minister of the day. It is a historic document that did much to galvanise support for Aboriginal rights. Today it is exhibited at the Melbourne Museum.

Cummeragunja walk-off

Jack played a key role in the famous Cummeragunja walk-off in 1939. Having returned to the old mission in 1938, he was dismayed by its poor management and food shortages. Despite appeals to the government, the situation deteriorated further and Jack encouraged the residents to leave. Around 200 people did, and although the event resulted in Jack's arrest, it became a powerful symbol of Aboriginal defiance.

Inspired a new generation of Aboriginal leaders to carry on the fight

Prior to World War II, military regulations officially excluded Aboriginal people from enlisting in Australia's armed forces. While many still served during World War I, this often required them to conceal their heritage. In 1939, Jack successfully campaigned to have the rules changed, before enlisting in the army himself. He went on to serve in Palestine and Egypt as a private, until a piece of shrapnel damaged his knee. Discharged in 1942, Jack joined the Civil Construction Corps.

After the war, notwithstanding his military service, the Aborigines Protection Board removed 6 of Jack's 7 children from where the family was camped in northern New South Wales. His 5 daughters ended up in the Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls, however Jack mounted a daring retrieval of his son – who was taken to the town of Bomaderry – and escaped with him to Cummeragunja. By 1946, Jack was suffering from post-war depression and had separated from his wife. He relocated to Victoria, eventually settling in Melbourne, where he worked for the Aboriginal community in Fitzroy, ensuring that Aboriginal people had adequate representation when appearing in court.

In the last years of his life, Jack established the Australian Aboriginal Elders Council of Victoria, of which he was president and reunited with William Ferguson to oppose the British atomic testing at Maralinga in South Australia. Sadly, he was killed in car accident in 1957. However, Jack left behind a rich legacy that inspired a new generation of Aboriginal leaders to carry on the fight in his name.

Updated