- Inducted:

- 2013

Jock Austin was a charismatic Gunditjmara man and one of the most revered leaders of the Aboriginal community in Victoria. He recognised and nurtured the unique sporting prowess of Aboriginal people and promoted sport not only as a means to improve health and wellbeing, but also as a way to restore pride and purpose to the lives of the most disadvantaged.

Born under a gumtree at Framlingham Aboriginal Reserve in 1938, Jock was the son of Ella Clark and Cyril Austin. He grew up surrounded by a large extended family that included 11 siblings and many more cousins. Jock attended a local state school but left to find work as soon as he was old enough. One of his earliest jobs was cutting timber with his uncles.

From a young age, Jock displayed immense talent at sport, particularly football and boxing. At the time, there were several boxing troupes that travelled throughout regional Victoria competing in circus-like tents. Many of the most popular fighters were Aboriginal men, who became Jock's childhood heroes. He eventually convinced a passing troupe, managed by a larger-than-life character named Major Wilson, to employ him. In the years that followed, Jock toured agricultural shows, sharpened his technique as a boxer and earned a place in many stories of legend.

Jock moved to Melbourne in the late 1950s, where he joined the growing Aboriginal community in the inner city suburb of Fitzroy. He worked as a boilermaker for a time, and also had a job laying tram tracks. Jock continued to excel at boxing and football. He met Patricia Prior and together they raised their two children, Troy and Thelma. Jock was a proud family man. He affectionately referred to his mother as 'Mummy Ella' and his children recall attendance at her Sunday dinners as being non-negotiable.

Although his life was not without its struggles, Jock overcame them and was determined to help others do the same. To that end, he considered physical fitness and good health to be crucial. Jock was appointed sports co-ordinator at the Victorian Aboriginal Health Service (VAHS) after its establishment in 1973 and subsequently implemented a range of social, sports, and health programs for the organisation.

In response to the drug and alcohol problems affecting young people within his community at the time, Jock proposed an idea for a gymnasium and youth club. He believed it would empower young people and get them off the streets. With the support of VAHS management, he leased a venue and opened the Fitzroy Stars Aboriginal Community Youth Club Gymnasium in 1982. Its success led to its rapid expansion. Jock eventually secured funding from the Aboriginal Development Commission to purchase a building in Gertrude Street, Fitzroy. The organisation, which is now known as Melbourne Aboriginal Youth, Sport and Recreation (MAYSAR), is still located there today.

The new youth club gymnasium provided young Aboriginal people with a place to learn, train, and connect with peers. While Jock was a highly-regarded boxing trainer, the activities on offer ranged from cricket and netball to kick boxing and aerobics. However Jock had created far more than just a youth club gymnasium. It was a safe and welcoming place that offered shelter and structure to anyone who sought it: black or white, young or old. The youth club gymnasium became an important focal point for the entire community and Jock was its heart, a tough but adored father figure.

Jock believed in the value of education and strived to help his people understand their history and the world around them. He worked with young offenders and wards of the state, providing them with guidance and support. Over the years, Jock and his wife opened their home to countless young people in need. Together they also hosted annual Christmas lunches for Fitzroy's poorest, including the 'parkies' who gathered in local parks and lanes.

A passionate footballer, Jock had a long association with the Fitzroy Stars Football Club (FSFC), an Aboriginal team established in the early 1970s. He served the club in a variety of roles, including as coach and president, and oversaw the establishment of a junior club in 1978. He was also the driving force behind the club's revival after it was left without a league in the 1980s. Despite knock backs from several inner city leagues, Jock persisted, until the FSFC found a place in the Melbourne North Football League in 1989. He also worked hard to establish what is today known as the Sir Doug Nicholls Sports Oval at the Aborigines Advancement League. A pavilion at the oval bears Jock's name.

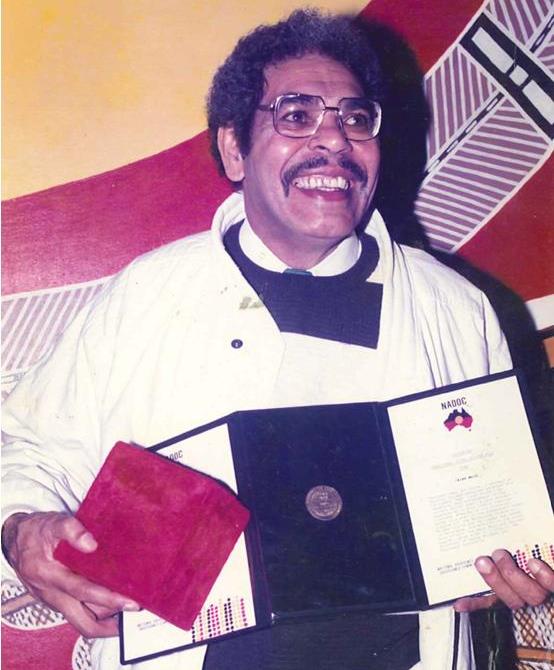

Recognised as a community leader of considerable influence, Jock held positions at the Aborigines Advancement League and VAHS. He was director of the Victorian Aboriginal Youth, Sport and Recreation Co-operative and a board member of the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service and the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency. Jock represented Victoria on the board of the National Sports Foundation and was a delegate to the National Aboriginal Sports Council when it was established in 1986. In 1988, he received a National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee (NAIDOC) award for his community work.

Over the years, many prominent Aboriginal people have reflected on the positive impact Jock had on their lives. These include singers Kutcha Edwards and Archie Roach — who dedicated his first album to his cousin, Jock — as well as the world champion boxing great Lionel Rose MBE, another cousin. Jock was a figure of reconciliation and thought of by all as a gentleman: someone who could communicate as easily with workers at the docks as he could with government ministers, or Aboriginal Elders in central Australia. After Jock passed away in 1990, more than a thousand mourners attended his funeral service, a powerful testament to the esteem in which he was held.

Jock Austin was an impressive figure, described as physically imposing. Most imposing of all is the legacy he has left behind, one of a lifetime dedicated to helping his people.

Updated