- Inducted:

- 2020

A pivotal figure in the early history of Aboriginal-European relations in Victoria

Billibellary was a Wurundjeri Woiwurrung ngurungaeta or clan headman. He was born around 1799 in what is now known as Melbourne.

More precisely, Billibellary was ngurungaeta for one of the 3 groups that formed the Wurundjeri-willam patriline of the Wurundjeri-balluk clan. Billibellary’s mob has connections to the Maribynong River (Mareingalk) up to Darebin Creek in metropolitan Melbourne, as well as Mount William (Wil-im-ee Moor-ring), approximately 40 kilometres to the north of Melbourne. Wil-im-ee Moor-ring was the leading greenstone quarry prior to white settlement, as its volcanic diorite was highly regarded for axe heads.

Tall and agile, Billibellary was an insightful leader who sought to negotiate on behalf of his people instead of using physical force towards newly arrived Europeans. In essence, Billibellary chose conciliation over warfare. He was considered a kind, wise and thoughtful statesman with astute diplomatic prowess. Known as the Chief of the ‘Yarra Yarra tribe’ to early European settlers, he had 2 wives - Konningurrook and Moorurrook - and was the father of 8 children, including Simon Wonga and Tommy Munnering (also known as Munnwering).

Billibellary was one of 8 Aboriginal leaders who met with John Batman on 6 June 1835 and signed his agreement to acquire a vast tract of land in the Port Phillip Bay (Nairm) area. Historians have proposed that the clan-heads perceived Batman’s negotiations as an eagerness to begin the required Tanderrum ritual, a ceremony enacted by the nations of the Kulin people that ensures official protection to outsiders, as well as short-term entry and use of land and its resources, under the proviso that hosts shall not be impacted by the presence of their guest. But John Batman and the many Europeans that followed were not temporary guests and their presence would irrevocably alter the lives of these Aboriginal leaders and their people.

With growing resentment Kulin warriors attacked European campsites the following year, yet Billibellary persevered with diplomacy and used such interactions to become proficient in ‘imperial literacy’. This approach was by no means an act of surrender, as Billibellary learned to speak English and carefully observed European ways to better understand the interlopers. Such undertakings suggest he was exploring ways to control the situation, but things were stacked heavily against Billibellary and his people.

Within another 4 years there would be 4,000 Europeans residing in Melbourne. Soon, the number of sheep and cattle farmers would swell, land would be fenced and access restricted, livestock herds would devour crucial food sources, and the loss of habitat would permanently upset the wellbeing of native animals. This spelt disaster for the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung and other Kulin people. Clans quickly became ‘refugees in their own Country’ and the regulation of Aboriginal space, bodies and territories was set in motion.

The Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate was established in 1839 to safeguard the rights of Aboriginal people, as well as introduce them to Christianity and the ways of the white man. The Protectorate system was founded on the deeply interventionist belief that conversion to Christianity would improve the lives and welfare of Aboriginal Victorians. Efforts to dictate rigid measures on First Nations peoples is a British settler narrative and such confidence was built on white supremacy and the firm refusal that First Nations peoples would favour their own belief systems, as well as their own economies, teachings, laws and medical practices.

William Thomas, an English teacher and Wesleyan Christian, was appointed Assistant Aboriginal Protector for the Central Protectorate District (Western Port). This area encompassed the Melbourne township, extending to the Yarra and Plenty valleys, as well as Western Port and the Mornington Peninsula to Wilson’s Promontory. Although William Thomas would dedicate the rest of his life to the welfare of Aboriginal people and learnt Kulin languages and cultures, his Christianity largely limited his appreciation and understanding of First Nations peoples.

Thomas and Billibellary’s destinies were profoundly intertwined until the untimely death of Billibellary. Although they were very friendly with one another, their relationship was in no way equal under British law and Billibellary rejected his new-found standing of subordination and asserted his and his people’s intrinsic sovereignty and rights. He demonstrated this, for example, through the Narre Narre Warren walk-off.

When, in September 1840, Superintendent Charles La Trobe attempted to ban Aboriginal people from entering the township of Melbourne, it was Thomas who asked the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung and Bunurong people to find an alternative site to relocate to. The place that was chosen was Narre Narre Warren, but soon after their arrival relations with the Protectorate grew increasingly acrimonious due to lack of food, land hunger of settlers and the everyday hostility of Europeans.

Billibellary expressed his concerns and resentment in an energetic address to his people after months of ongoing and often forceful displacement and reneging of agreements. The next day, many residents walked off the station alongside Billibellary ‘in a sovereign withdrawal of cooperation with colonial authorities’. Eventually all residents returned to the station, but this walk-off gave rise to a quietly insistent campaign that asseverated the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung people’s rights to freedom of movement in their own Country.

As ngurungaeta, Billibellary also developed a vision for the future. He requested land for his people to regain self-determination so that they could farm with the same rights as Europeans but keep culture strong. This steadfast idea would take root over the next two decades and after several attempts at autonomy, an Aboriginal settlement was established at Coranderrk in 1863. Unfortunately, Billibellary did not live to see that moment. He died of respiratory disease on 10 August 1846 at the Merri Creek Protectorate Station located in what is now the Yarra Bend Park.

Billibellary was a vital statesman during a time of great adversity for the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung and other Kulin people. He thrived under the old ways and then became a key witness to the drastic changes that unfolded on his Country when Europeans established a place that they would come to call Melbourne.

He approached such encroachments with grace and conciliation, always working for the rights and welfare of his people, even though his standing in a new society diminished significantly. Ultimately, Billibellary remained resilient and did not sway from his convictions. His perseverance and diplomacy ensure his name and fundamental contribution to our shared history will never been forgotten.

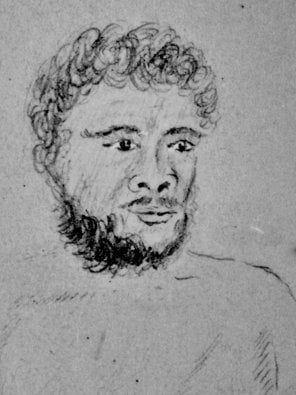

Portrait (detail) of Billibellary by William Thomas.

Brough Smyth Papers, La Trobe Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria.

Updated